Uk Free Range Production of Beef Per Year

Thousands of British cattle reared for supermarket beef are being fattened in industrial-scale units where livestock have little or no access to pasture.

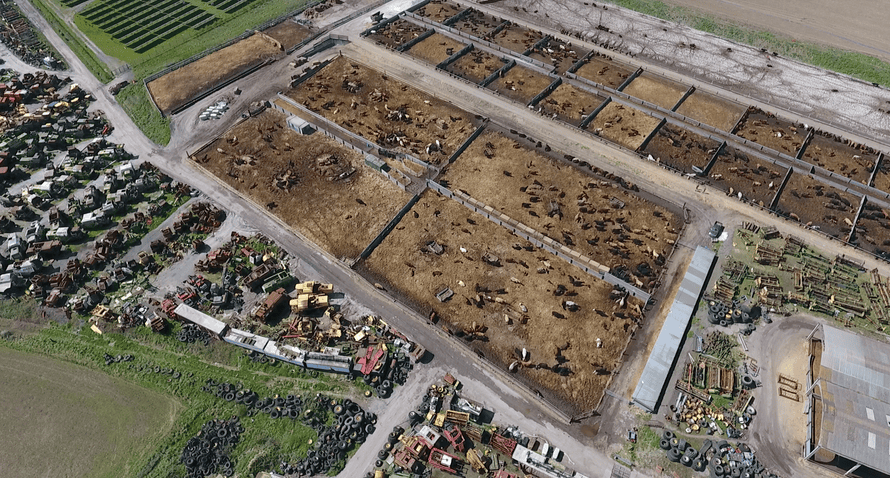

Research by the Guardian and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism has established that the UK is now home to a number of industrial-scale fattening units with herds of up to 3,000 cattle at a time being held in grassless pens for extended periods rather than being grazed or barn-reared.

Intensive beef farms, known as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs) are commonplace in the US. But the practice of intensive beef farming in the UK has not previously been widely acknowledged – and the findings have sparked the latest clash over the future of British farming.

The beef industry says that the scale of operations involved enables farmers to rear cattle efficiently and profitably, and ensure high welfare standards. But critics say there are welfare and environmental concerns around this style of farming, and believe that the farms are evidence of a wider intensification of the UK's livestock sector which is not being sufficiently debated, and which may have an impact on small farmers.

In contrast to large intensive pig and poultry farms, industrial beef units do not require a government permit, and there are no official records held by DEFRA on how many intensive beef units are in operation.

But the Guardian and the Bureau has identified nearly a dozen operating across England, including at sites in Kent, Northamptonshire, Suffolk, Norfolk, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. The largest farms fatten up to 6,000 cattle a year.

Drone footage and satellite images reveal how thousands of cattle are being kept at some sites in outdoor pens, known as corrals, sometimes surrounded by walls, fences or straw bales. Although the cattle will have spent time grazing in fields prior to fattening, some will be confined in pens for around a quarter of their lives, until they are slaughtered.

Supermarket demand is believed to be, at least in part, driving the trend. In addition, some smaller and medium-scale beef producers have struggled to farm profitably in recent years, with sometimes tight margins and fluctuating costs. Most of the units identified are believed to have grown incrementally, rather than setting up from scratch.

A number of retailers, including the Co-op, Lidl and Waitrose, are among those found to be sourcing beef from UK intensive industrial scale farms, most of which are privately owned but sell to beef processing companies, which in turn supply retailers.

Chris Mallon, director of the National Beef Association (NBA), the industry trade body, said the reason the largest units have come about was purely down to "efficiency".

"What we're talking about here is commercial production, for feeding people. It's not niche market. A lot of this will be on supermarket shelves – that's where it's coming into its own. In the catering side as well, they'll be doing it," he said.

"One of the things we've seen over the years is supermarket domination of the beef trade. What they want is specification, size of cuts, size to fit certain packaging, size of roasts – this has all become incredibly important."

But he cautioned that farms dedicated to fattening cattle had always been bigger than those rearing them, "so actually having higher concentration of feeding cattle on units [isn't new].

"The difference is we're getting some larger units now and that will be because of economies of scale … if you can give the people you're supplying a constant supply of cattle that are in the right specification, that makes you more valuable. And that's one of the reasons we've seen a move towards it."

Dr Jude Capper, a livestock expert who has studied intensive beef units in the US and elsewhere said that due to economies of scale "it's almost inevitable that a larger farm can produce a greater quantity of a more affordable product – we see this in almost all agricultural sectors globally, just as we do in other industries".

The Guardian and Bureau last year revealed that 800 poultry and pig "mega farms" or CAFOs have appeared in the British countryside in recent years, some housing more than a million chickens or about 20,000 pigs.

Following the revelations, the environment secretary, Michael Gove, pledged that Brexit would not be allowed to result in the spread of US-style agribusiness: "I do not want to see, and we will not have, US-style farming in this country," he said in a parliamentary statement.

Although the number of beef units is tiny in comparison with intensive poultry or pig farms, the latest findings have further fuelled fears that the UK could be embracing industrial-scale practices.

Caroline Lucas, MP for Brighton Pavillion, said the farms were "gravely concerning" and that "with Britain hurtling towards Brexit, and with our animal and environmental protections facing an uncertain future, I'm worried that we could end up adopting more of this US-style agricultural practice".

Richard Young, Policy Director at the Sustainable Food Trust, said: "Keeping large number of cattle together in intensive conditions removes all justification for rearing them and for consumers to eat red meat... More than two-thirds of UK farmland is under grass for sound environmental reasons and the major justifications for keeping cattle and eating red meat are that they produce high quality protein and healthy fats from land that is not suitable for growing crops."

Young added that that smaller scale beef farmers might feel the impact, as larger farms were likely to be "more efficient in purely economic terms", allowing the supermarkets "to drive down the retail price of beef below the price at which more traditional farmers can produce it. As a result they go out of business."

The changing face of traditional UK beef production

Beef production in the UK typically involves three distinct stages - calf rearing, growing and fattening - with many farms specialising in one part of the rearing process. Cattle may move between a number of different farms during their lifecycle. (A smaller number of farms rear cattle from birth and keep them on the same farm until being sent to the abattoir.)

After spending time on pasture many cattle are moved to dedicated "finishing units" and are typically housed in barns or grazed whilst being fattened ahead of slaughter, often for around 6 months. Many are fed specialist diets designed to encourage weight gain.

But in the US, much beef fattening takes place in "feedlots" with cattle held in vast outdoor pens where the largest facilities confine up to 85,000 livestock. Such "feedlots" have proved controversial in the past, both because of their size and because many cattle were given hormones and antibiotics, sometimes to encourage rapid growth. (Such practices are not permitted in the UK).

Despite acknowledging the arrival of intensive beef farming in the UK, experts reject the notion that the British beef sector will see a wholesale shift towards farming on a US-scale.

"Are we likely to see huge – 100,000 head – feedlots? No. We don't have the market, infrastructure or public demand for them," said Capper. "However, could we make better use of male calves from dairy farms by rearing them for beef in feedlot-style operations, using feeds that we cannot [or] will not eat, such as by-products from human food crop production? Absolutely – some beef producers are already doing this."

Caroline Lucas called for the system of permits to be tightened up, and said "the Government should be officially recording the number of feedlots rather than letting reporting slip through a loophole … we need a proper debate in this country over what kind of agriculture we want in the future."

A spokesperson for DEFRA said that "beef farms are regulated in exactly the same way as any other farms". But it later acknowledged that "Defra does not have a database of feedlot style units...The Cattle Tracing System can provide figures on the number of holdings split by premised type e.g. Agricultural Holding, Slaughterhouse, Market etc. and the number of animals registered to each. However, it does not hold any data in respect of the feeding practices on the holdings."

Waitrose said of its own supplier: "Animal welfare is of the highest importance to us and a large farm does not equal poor animal welfare standards. The farm is run under a bespoke environmental management plan in conjunction with Natural England. All the cattle graze the marshes during the summer season then during the winter months, when the grass is dormant the cattle are bought back to the yard when the finishing/fattening cattle are housed in covered sheds. For clarification the length of grazing season is weather dependent, once the grass stops growing the cattle need to be yarded and fed a forage based ration in accordance with animal welfare and best practice."

A spokesperson for the British Retail Consortium said: "Our members take their responsibilities to animal welfare very seriously and work closely with trusted suppliers so that high welfare standards are upheld. They have strict processes in place and will thoroughly investigate any evidence of non-conformity to ensure that any problems are immediately addressed."

The Guardian approached several of the largest units but all declined to comment.

Some in the beef industry itself have expressed unease about the intensive farming system. Russ Carrington, of the Pasture Fed Livestock Association, said: "It is sad that the travel towards cheap, de-valued food has led to the removal of livestock from fields. There is a very different, more sustainable way of producing high quality beef which is also considerably healthier for humans to eat – 100% grass-fed and grain-free, which has lower total and saturated fat content, a better ratio of omega 3 to omega 6 fatty acids and more vitamins and minerals, which comes from the diverse pasture they eat."

Pressure group Compassion In World Farming (CIWF) have raised concerns that some cattle held at in "feedlots" are kept in "high stocking densities" with little or no shelter or shade and "no dry ground to rest on." The group says it believes "cows belong on pasture".

In response Dr Jude Capper said: "In my experience at feedlots all over the world, I've yet to see any welfare issues that are inherent to the system. If we are to assume that cattle must be able to graze to lead a 'happy' life, then confinement may be regarded as an issue. However, I've yet to see this being backed by [any evidence-base]."

Evidence compiled by the Bureau and Guardian suggests that most intensive beef farms appear to operate to high welfare standards.

Chris Mallon said: "Cattle actually will be very happy in [these systems]. Cattle in the wild don't build nests for themselves or hide in caves, they're an outdoor animal and I think we've got to remember that."

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/may/29/revealed-industrial-scale-beef-farming-comes-to-the-uk

Post a Comment for "Uk Free Range Production of Beef Per Year"